A rise in extreme heat over the last five years is endangering a growing number of pregnant women and their babies.

To continue reading, subscribe to Eco‑Business.

There's something for everyone. We offer a range of subscription plans.

- Access our stories and receive our Insights Weekly newsletter with the free EB Member plan.

- Unlock unlimited access to our content and archive with EB Circle.

- Publish your content with EB Premium.

According to a new paper by Climate Central, a climate science non-profit, the number of days of the year that were dangerously hot for pregnant women doubled between 2020 and 2024 in 90 per cent of 247 jurisdictions studied worldwide.

High temperatures during pregnancy increase the risks of complications such as stillbirth, gestational diabetes, and premature labour, which can lead to lifelong health impacts in children.

Researchers compared the number of unhealthily hot days of the year for pregnant women – which they labelled “pregnancy heat-risk days” – with the number of unhealthily hot days caused by man-made climate change in 247 jurisdictions between 2020 and 2024, which was the hottest year on record.

They found that man-made climate change was responsible for at least one month’s worth of pregnancy heat-risk days every year in one third of the territories studied.

In Asia, one-fifth of analysed countries (11 out of 57) experienced at least one additional month of pregnancy heat-risk days on average each year due to climate change, with Southeast Asia the most heavily affected sub-region.

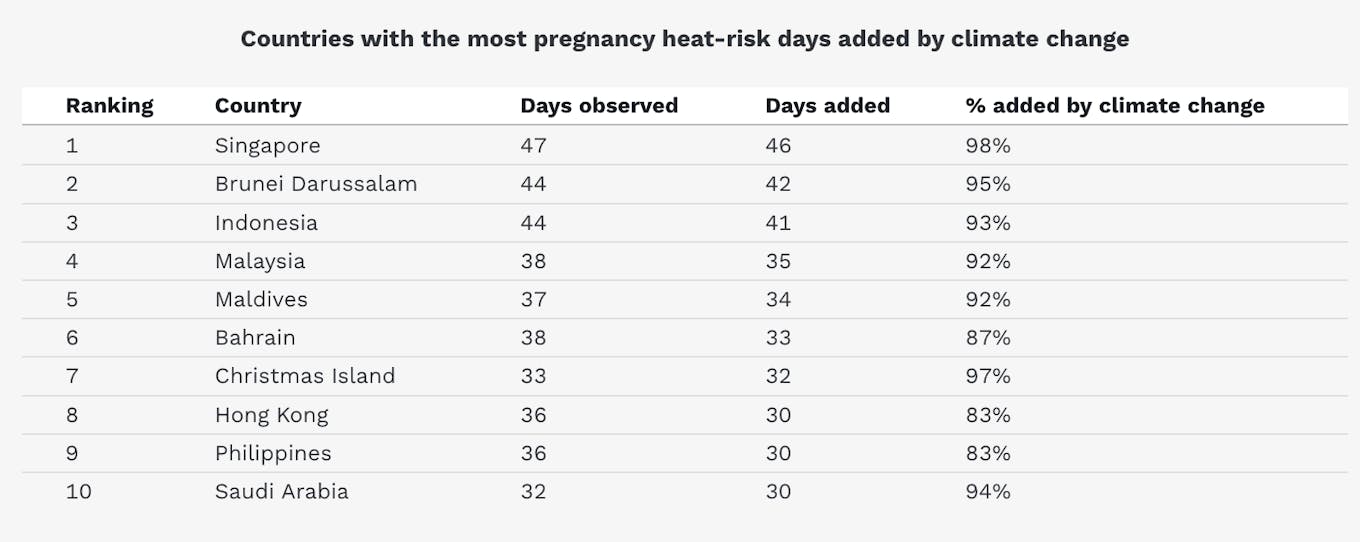

Singapore was found to be the region’s most severely affected country. Between 2020 and 2024, an average of 47 days of the year were perilously hot for pregnant women, with 46 of those excessively hot days attributable to climate change.

Brunei was the next most severely affected Asian territory, with 42 out of 44 pregnancy heat-risk days attributable to climate change, followed by Indonesia (41 out of 44 days) and Malaysia (35 out of 38 days).

City-wise, Indonesia’s Batam, which borders Singapore, was found to be the region’s most dangerous for pregnant women, followed by neighbouring Singapore and Zamboanga in the Philippines.

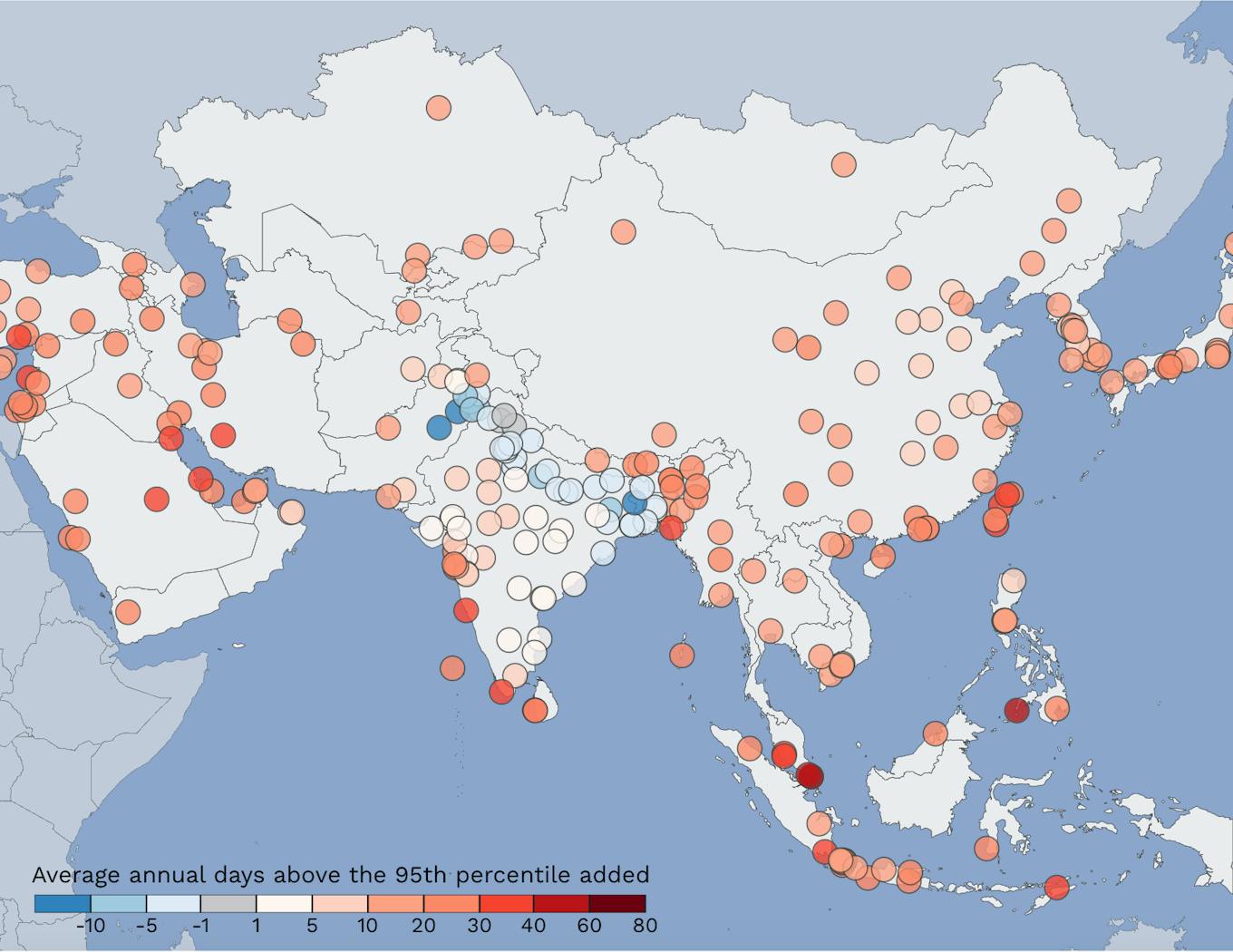

Pregnancy heat-risk days added by climate change, by city. The Indonesian city of Batam was the region’s most dangerous for pregnant women, followed by neighbouring Singapore and Zamboanga in the Philippines. Source: Climate Central

Dr Kristina Dahl, vice president for science at Climate Central, said that climate change is increasing extreme heat and stacking the odds against healthy pregnancies, especially in places where healthcare is hard to access.

Developing regions with relatively poor access to healthcare, such as Southeast Asia, Central and South America, and sub-Saharan Africa are exposed to the highest number of pregnancy heat-risk days.

Asian countries with the most pregnancy heat-risk days added by climate change [click to enlarge]. Source: Climate Central

Prosperous Singapore, which saw its fertility rate drop to a record-low last year, is an outlier as Asia’s most at-risk nation for pregnant women, although the majority of the population has regular access to airconditioning and quality healthcare.

The study does not link pregnancy heat-risk to fertility, although the effects of high temperatures on reproductive health are well studied.

Climate-induced heat stress – that is, when the body cannot cool down through perspiration – results in lower sperm count and concentration among men, according to a 2024 study by the Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine at the National University of Singapore.

Other studies have shown that warmer temperatures can damage women’s eggs and disrupt the ovulation cycle, while also harming the development of the formed embryo.

Climate change can also affect the psychological desire to start a family. A study conducted in 18 African countries found that women exposed to abnormal environmental conditions were less willing to have children.

Dahl noted that changes in fertility rates and population trends have many different causes, from the presence or absence of social safety nets to the educational opportunities available for women, and climate change may influence those trends. However, she stressed that the impacts on maternal and infant health are likely to worsen if insufficient action is taken to reduce fossil fuel consumption.

According to a population study by The Lancet, three-quarters of countries will not have high enough fertility rates to sustain their population size by 2050, and 97 per cent of countries will have a similarly unsustainable fertility rate by the end of the century.

The United Nations expects the world’s population to peak at 10.3 billion by the mid-2080s, up from 8.2 billion people in 2024, and decline gradually to 10.2 billion by 2100. The UN’s projections, made in July last year, are 6 per cent lower than anticipated a decade ago, as a result of a rapidly declining fertility rate in high and middle-income countries such as China, South Korea, Italy and Spain.